William Shakespeare once said: “Life is a tale, told by an idiot… signifying nothing.” I often wonder if Shakespeare was ever incarcerated, because I am, and I feel this way every day.

I like to consider myself an optimist. But behind that optimism lies this feeling that I just can’t shake off. It’s the feeling of worthlessness and uselessness. It’s an utter negativity that’s at odds with my deep religious beliefs. If I look through a religious prism, I know that this sentiment is blasphemous. No self-respecting religious person would adhere to the notion that our lives signify nothing.

If I were to mention this to a fellow Muslim, for instance, he or she would surely quote me a hundred verses from the Qur’an and the sayings of the Prophet that explain this concept away. “It will all make sense at the end,” is the belief we’re taught to hold on to. I’m sure that Christians and Buddhists and Hindus will likely say the same. Even an atheist who argues about the fallacy of believing in the existence of a God would probably disagree with the idea that life signifies nothing.

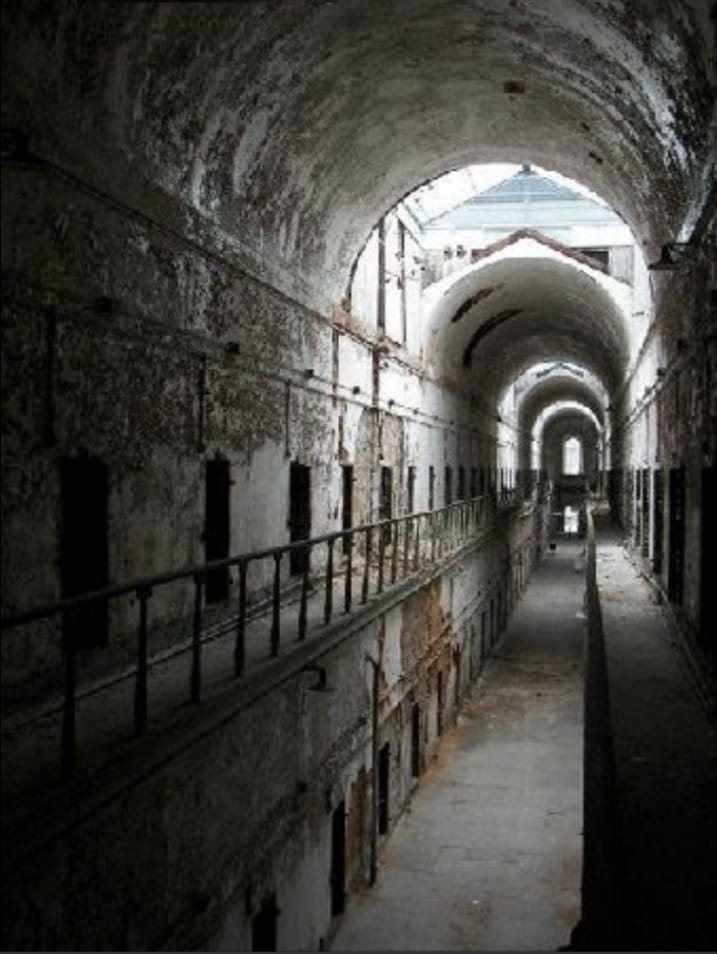

Now ask a person who is locked up behind bars, where human existence is abstract at best, almost like living on the dark side of the moon. To a person like me, sentenced to 150 years, the phrase “life is a tale, told by an idiot… signifying nothing” is more than a concept in literature. It is an anthem.

I live in a cell that measures 12 feet in length and seven feet wide. The walls are painted a light gray, sort of matching my mood. I could have chosen a dark gray color but I chose the lighter shade. I try to be an optimist, after all. I don’t hang anything except two calendars on the wall. Pictures of loved ones would only hurt too much on my bad days and I don’t want to invite any comments from the other people in this place that might trigger a fight. So there’s nothing to look at when I sit on my bunk, other than a long, thin plexiglass window, through which I see the world when I choose to look.

When I do look out the window, the feeling is almost surreal, as if I’m doing something forbidden. As if the mere act of looking outside is sinful, somehow. The scenery sucks, anyway, because my view of the world is hindered by the sight of the sprawling prison itself. I mean who wants to see castle-high walls and chain-linked fences decorated ornately with barbed wires all day? I do enjoy looking at the sky, though. Finding star constellations has been one of my hidden hobbies since I was a child. My name is Tariq, after all. It means North Star.

My life is far from celestial, though. I sometimes think about the man I was before I was incarcerated. I come from an immigrant Pakistani-American family. We came in pursuit of the American dream and, for the most part, my family was able to achieve that success. Obviously, with the exception of what happened to me. I was the first born son, the older brother. Before prison, I went to college and started my own business. I worked hard to supplement my father’s income and to be there for my younger brother. I had meaning then. I had purpose.

Now, the smallest interactions with my family can make me feel worthless, although that is never their intention. Case in point: I just got off the phone with my brother. I couldn’t ask for a better one as he is the best man I have known in my entire life. I daresay that all of the dictionaries in the world should just paste his photo under the definition of the word brother. He is a real estate agent now, a husband and a father. He takes care of my parents. His life is busy but whenever I call, he puts everything on hold to see what I need.

In this case, I needed him to do some research for me. It was a simple request that I would have been able to do myself if I was on the outside. But we don’t have the ability to search on the internet. So, instead my brother made his high-end client wait and began to search for me. He did his best to pay attention to my instructions and requests. But I could feel his agitation building up the more I asked of him. As always, he didn’t complain. The only thing he said before ending our conversation was “I wish you get out soon, bro.”

And that was enough for me. There was nothing in that remark other than his earnest wish that I come out of this prison. But in his voice and his tone, I heard pain and I heard resignation for my plight. I heard the sadness that comes from his putting his life on hold, even for a short amount of time, to help me whenever I had a small request. I felt the weight of being a burden.

Prison is designed to inhibit all avenues of your dignity. It makes you feel like a beggar. And that is exactly the way things are meant to be inside here. Prison makes you a person in perpetual need of others. For a person like me, who was always the helping type on the outside, having to ask for help with even the simplest tasks goes against everything I am. Every request for help is a favor which I am unable to repay. So, that brings me back to feeling like a beggar. It’s a feeling of worthlessness.

This is my existence in prison. These are the thoughts I have as I sit alone on my bunk or see the five storage bins that contain all of my belongings. Three of those bins, which are about the size of your average laundry bucket, contain my documents from my criminal case. Of all the property I own right now, legal paperwork makes up the majority of it. I’m sometimes astonished by the amount of paperwork I’ve accumulated over the last 16 years trying to appeal my case. That process has also added to my sense of meaninglessness.

I sometimes think it would have served me, the taxpayer, my family and trees, in general, better if they had just told me at my conviction that I should play the lottery instead of filing for appeal. I wonder at times if I die in this cell today, would they recycle all of this paper or would they just throw it in the garbage. Useless paperwork for a life rooted in uselessness.

Every day I contemplate whether it is worth it to leave my cell. Because at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter what I do. Whether I’m good or bad, the day will end the same, exact way. A door will slide shut and I will be back in my cell. I wonder if any of this experience means anything or whether Shakespeare had it right all along. But then I consider whether I even have the right to wonder about anything at all. I’m just a convict rambling from the dark side of the moon. Is anyone even listening?

-By Tariq MaQbool